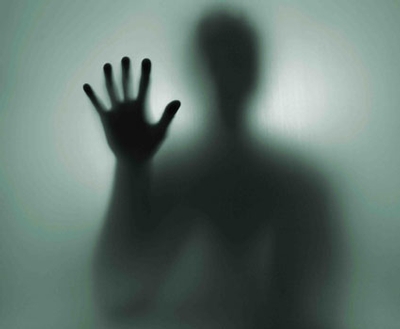

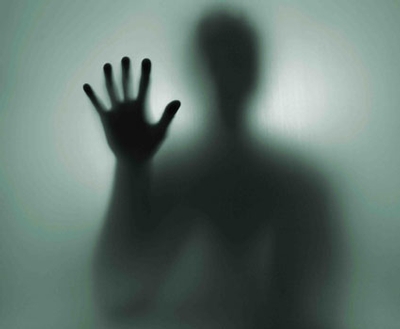

In the old black-and-white plate, the pool of shadow on the left of the ghost’s face uncurled its legs to scuttle for the margin and the cluttered desk beyond. I shrank back in my seat and, no word of a lie, I genuinely felt it. It was over in a second when I realised it was just a garden spider come indoors out of the cold, what had been camouflaged against the dark bits of the photo, but I really felt that sort of tingle up the spine that all my clients go on about, so I know what they’re saying. I can empathise with them. It’s not all acting.

In the old black-and-white plate, the pool of shadow on the left of the ghost’s face uncurled its legs to scuttle for the margin and the cluttered desk beyond. I shrank back in my seat and, no word of a lie, I genuinely felt it. It was over in a second when I realised it was just a garden spider come indoors out of the cold, what had been camouflaged against the dark bits of the photo, but I really felt that sort of tingle up the spine that all my clients go on about, so I know what they’re saying. I can empathise with them. It’s not all acting.

Actually, to be perfectly honest, I think nine times out of ten it’s that gives us what I suppose you’d call a supernatural feeling: something turning out to not be what you thought it was. I can remember, I was only six or seven when I saw my first and only ghost. I was with Mum and Dad in the lounge of a seaside pub at night, standing there glued to the glass doors and gawping out into the dark, not thinking of anything in particular. Just then I saw this man walking across the car park of the pub away from me. He wasn’t any colour. He was all washed out and grey, and then I realised there were parts of him that I could see through. I could see the scrubby strips of grass, the bollards and the drooping lengths of chain that closed the car park in, through the black folds and shadows of his jacket. I thought, ‘It’s a ghost! I’m really seeing one!’ And then, and this was the most frightening bit, it turned its head and looked straight at me. It had got two blurry faces, one of them just slightly offset from the other, and it smiled in at me through the glass from out there in the night, and then it spoke my name. It’s like, I saw its lips move but I heard its voice as if it was right next to me, rather than outside in the car park. It said ‘Ricky? Would you like a Fanta?’

Obviously, it was my Dad, standing behind me in the lounge with his reflection superimposed on the dark outside. The business with two faces turned out to be caused by double glazing, but just for a second there, you know? I’d thought it was a ghost and that it proved all of the stories that I’d heard from other kids at school. I think it made me cry and when I explained why, about the ghost and everything, Dad told me off and said I was like an old woman, getting taken in by all that superstitious rubbish. Always very level-headed was my father, and I probably take after him in that respect, although I never really liked him much. I was much closer to my mum, but then that’s very often how it is with boys, especially an only child. When Dad passed on I suppose Mum was my first audience, as well as being my most willing and my most appreciative. She thought the world of me, my mum. She gave a little gasp and filled up when I did his voice and said, ‘I always loved you, Irene.’

Knowing Dad, it was a safe bet that he’d never told her that in life, and when I saw the comfort that I’d brought that woman, my own mum, that’s when I knew I had a gift. That’s when I knew what Ricky Sullivan had been put on this earth for. Oh, there’ll always be the unbelievers and debunkers in the papers, on the telly or what have you and it does, it makes me angry when they say people like me are cold, unfeeling, just taking advantage and all that. I’m sorry, but if they could see the happiness in people’s faces, if they really thought about the service me and others like me are providing, giving people strength to get on with their lives when they’ve just lost a loved one, well, they couldn’t say the things they say. I’m sorry, they just couldn’t. I don’t have to justify myself.

I mean, do I believe all of the things that I tell people? In my heart, I can’t say that I do. But then, what about priests? You can’t tell me that all of them believe every last word of what they preach, but do they get called ‘ghouls in cardigans’ or ‘Vincent Price, but camp’? No. No, they don’t. That’s because people recognise all of the reassurance and the comfort that religion brings to people, and it doesn’t really matter if it’s true or not. Or doctors, it’s like doctors when they say that a placebo, that’s like, what, a sugar pill? That a placebo can work wonders without any side effects, but that they can’t prescribe them ’cause of all the medical red tape and ethics, health and safety, all that business. That’s me. I’m a spiritual sugar pill, but I do people good. I’m sorry, but I touch their lives.

And yes, I suppose you could say that I’ve done very well out of it, got the mortgage on this house paid off last year, but that’s not what I do it for. It’s not the money. How can I explain? It’s more the gratitude, the look on some poor widow’s face and knowing that you’ve helped them. That, to me, what can I say? That look’s worth more than gold. That’s my reward, right there.

Although this place is very nice, it must be said, with the old-fashioned furniture and all the books, the angel figurines along the mantelpiece, all that. It’s mostly for the clients’ benefit, same as the New Age music I’ve got on. It reassures them, makes them feel as if they’re in safe hands. No, no, it’s very comfortable. It’s very cosy, and especially now that the clocks have gone back and we’ve got these cold nights. If I peer out of the window at the park across the road it looks like one of them old-fashioned fogs tonight, where you can hardly even see the trees. It just makes me feel all the warmer, with the central heating turned up, standing here in this new cardigan that one of my old ladies knitted for me. Said I hadn’t charged enough for all the happiness I’d brought her, bless her, and she knew that I liked cardigans. A lovely lady. No, when I was little, what I liked best were the rainy, windy nights when I could lay tucked up in bed and think about all of the people out there in the cold, so that I could feel even snugger by comparison. I’m lucky in that that’s what my whole life’s like these days, very snug. Snug by comparison, you might say. Ah. There goes the phone. The landline, not my mobile, although even I have trouble telling them apart because the ring tone’s very similar.

‘Hello, there. You’ve reached Ricky Sullivan – the angel’s answering service. This is Ricky speaking. So, how can I help you?’

‘Um, hello. My name’s Dave, David Berridge. Look, I’ve...well, I’ve lost somebody, y’know, recently, and I was just...I don’t know. To be honest, I’ve been in two minds about if I should ring you up or not. I’ve never really been much of a one for all this, no offence, and I don’t even know if they’d approve, the person that I’ve lost...’

Just judging from the accent he’s a local man, probably lower middle-class and in his, what, his forties? Early fifties? He sounds lost, as if his life’s just fell to bits and nothing makes sense to him anymore. He’s calling out for help, and I’ve already heard enough to know that as clients go, this one is classic Ricky Sullivan. You can tell quite a lot about a person just from speaking to them on the phone. I’m writing down his full name on my jotter even as I’m talking to him.

‘Mr. Berridge, let me stop you right there. I prefer it if vessels of light...that’s what I call my clients...if vessels of light don’t tell me anything about themselves before they come in for a consultation, if that’s what you should decide to do. That way I get a clearer reading of their aura, without any preconceptions, and it’s fairer on them. What I always say is, if a person has a genuine psychic gift, why should you tell them everything? They should be telling you! That way, you can judge for yourself if I’m the real thing or not. That’s only fair. We do get a few con men in this business, and that’s why I insist that the special people who’ve been brave enough to seek my help are treated properly and given credit as intelligent adults. I’m sorry, but that’s just the way I am. Now, if you should decide to come in for a consultation that’ll be just 50 pounds, or it’s 100 for a house call. No need to bring any money with you, you can pay me when you get the invoice in a week or two, and only if you think that what I’ve done in contacting your loved one’s worth that much.’

I used to ask less, but I found that people are more likely to believe in something if they’ve paid more for it. Mr. Berridge, he sounds half convinced already, though his manner’s very shaken and uncertain. I expect that he’s been through a lot. He ums and ahs a bit and then asks if he can come to the house and have a consultation, perhaps later, around eight or so? I tell him that’s fine, and that he can call by earlier if he likes, I shall be in all evening. It’s a little touch, but it makes everything feel more relaxed and casual. It puts people at their ease and makes them feel as though they’re in control of things, and that’s important when you’ve had a loss.

He thanks me and hangs up, and right away I fish out the old iPhone and look up the local paper’s website, scrolling through the last two weeks’ obituaries before I find the name that I’ve got scribbled on my notepad. ‘Berridge, Dennis, beloved brother of David, uncle of Darrell and Josephine, passed away quietly at home, November blah blah blah’, and after that there was one of those poems that they must get from a book, like Best Man’s speeches. I’m not criticising. People are entitled to their feelings, obviously, but I just feel it’s tacky and it’s inappropriate, I’m sorry but I do, especially when it’s about something as personal as someone’s death.

So, anyway, a brother, then. I check and see if Mr. Berridge is on Facebook, and it turns out I’m in luck. Just reading through the updates and then following up links to a few other sites, I’ve pretty soon got all the information that I need to make a good impression on the client when he turns up. From what I’m reading here they weren’t just brothers, they were twins. It’s hardly any wonder David Berridge sounded so shook up. They say they often share a psychic link, do twins, and when one of them dies it must be terrible. I can remember Ronnie Kray, the gangster, when he died and it said in the paper that his brother Reg had sent a wreath he’d made out ‘to the other half of me’. It must be dreadful, losing somebody so close. You’d be so vulnerable. Still, on the bright side, it makes all my prep work easier, only having the one birth-date to remember and with a good many details of their upbringing in common. And it says here they’re identical, so David’s Facebook photo will do me for Dennis, too: a very bland face with fine, mousey hair that’s going grey and starting to recede; a light dusting of freckles on the nose; lacklustre eyes and a slight overbite that makes his mouth look rabbity. He doesn’t look as if he’s got much to him, to be frank about it, although I suppose it might be a poor choice of photograph. That’s why I always make sure Jenny, she’s my press girl, I make sure that she runs all the pictures by me before sending them out anywhere. I don’t want any more of me with that little moustache I used to have. I mean, I’ve never looked like Vincent Price, that’s just ridiculous, but where’s the sense in giving people ammunition? Anyway, clean shaven I look younger.

Oh, now this is interesting. Dennis Berridge had a blog, apparently. Hmm. Flicking through the recent entries, I’m afraid I have to say...oh, now, that’s very negative. That’s very harsh...I have to say he doesn’t sound like someone that I’d have got on with. In the science stream at school, then working as a physics teacher until it all got too much for him and he took an early retirement this last April. He sounds like a very bitter man. He starts off ranting about the Americans, the Christians, how they’re saying that the Bible should be taught alongside evolution in the schools. Well, I don’t see what’s wrong with that, with putting both sides of the argument. Oh, here we go. It’s Richard Dawkins this and Richard Dawkins that. There’s all the old stuff about homeopathy, how can it work with the dilution and the rest of it, and I expect...yes, here we are. “Why isn’t Doris Stokes keeping in touch more often since she died? Surely she still has books to push?” That’s low. I’m sorry, that’s just low. I mean, the woman’s dead and she can’t answer back. Show some respect, that’s all I’m saying.

Thinking back, that must be what his brother meant when he said that he didn’t know if the departed would approve of him consulting me. No, no, I’ll bet he wouldn’t. I’ll bet Dennis would regard that as a bitter irony, the thought of someone like me having the last laugh. Wouldn’t he just?

I memorise all the important details...a Great Dane called Benji that both twins were soft on when they were eleven, things like that...and then I smarten up the front room for when Mr. Berridge calls. There’s not much that needs doing, just some little touches to create the proper atmosphere. I put the dimmers down a whisker and then light a joss-stick. I’m not sure what kind of incense it is technically. It’s that sort that smells a bit pink, if you know what I mean. I put a couple of my most impressive ghost books on the coffee table. There’s the Eliot O’Donnell Haunted Britain where the spider gave me a fright earlier, and a great big thing full of airbrushed angels, just there lying casually around as if I read them all the time when actually I’m not what you’d call a great reader. Even Haunted Britain, I just got it for the pictures, really. They’re very impressive at first glance. You take the monk, ‘PLATE II. PHOTOGRAPH OF A NOTORIOUS SOMERSET GHOST’. It’s a proper what-I-call old-fashioned spooky apparition, manifesting on the well-lit landing of a fancy house in Bristol. Only when you’ve looked at it a minute or two do you notice how the light that’s falling on the monk is coming from a different side to everything else in the picture, so that you can tell it’s a double-exposure. And of course, you have to ask yourself what the photographer (a Mr. A.S. Palmer, it says in the caption) would be doing setting up his camera and his lighting kit to take a picture of an empty stretch of landing. Still, like I say, it’s effective if you only catch a glimpse of it.

Was that the doorbell? With the background music that I’ve got on now, Rainforest Sounds, there’s some bits where it’s very tinkly, like what are they called, wind-chimes, and it’s difficult to tell if someone’s at the door or not. It’s only half-past seven so I shouldn’t think it’s time for my vessel of light yet, although I did say he could come early if he wanted. Even out here in the hallway, I can’t make out if there’s anybody there outside the frosted glass. It’s probably just shadows from my hedge, but I expect I’d better check and see in case it’s...

‘Hello. Sorry, didn’t mean to startle you. Would you be Mr. Sullivan?’

God, Ricky, get a grip. First it’s a spider, and now this. I’ve heard of being highly strung and sensitive, but this is being an old woman like your dad said. Still, I make a good recovery.

‘Yes. Yes, I am. I’m Ricky Sullivan, lovely to meet you. I hope you’ve not stood here long, only I had some music on and wasn’t sure if I could hear the bell or not. You must be Mr. Berridge.’

He’s just like his Facebook picture, except he’s a bit more drawn and crumpled-looking since he had that took, a bit more haggard, which is the bereavement, I expect. He’s standing framed there in the open doorway, letting all the cold in. He looks up and manages a weary little smile, bless.

‘Mr. Berridge, yes, that’s right. And no, I’d only just turned up. I hadn’t even had a chance to ring the bell. You must have had one of those feelings that you fellers have.’

Well, there’s a stroke of luck. He’s half convinced and he’s not even in the door yet.

‘Oh, well, it’s not much, but there’s times when me having a God-given gift can come in handy. Anyway, come in the warm. We’ll see what I can do to help you, shall we?’

He sidles in past me, still with that self-deprecating smile, and I shut the front door behind him. It’s that cold outside that you can feel it in the hallway, even with the heating up. There’s no wind, and the fog’s just hanging there like rubbed-out smudges on a pencil drawing. He goes through into the front room and sits down upon the sofa without taking his long mac off, which gives the impression that he’s not anticipating staying very long. Well, we’ll see about that.

‘Mr. Berridge, can I just say that when you walked in, I got a very strong impression. Stronger than I usually pick up off of my regular vessels of light. You’ve recently been separated from somebody, am I right? Not just somebody close, but someone who was so close to you that I can’t even imagine what it must have been like. No, no, let me finish. I’m getting a letter ‘D’ and what I think might be a name? Denzel? Is that right? Wait a minute...no. That’s not right. No, it’s Dennis. Definitely Dennis. And the picture that I’m getting...no, that must be wrong. That can’t be right. I’m sorry, Mr. Berridge, but I think I’m going to have to let you down. I must be having an off night. I’m trying to get a picture of your loved one, but all I can see is...well, it’s you, basically.’

Oh, yes. That’s got his attention. He looks up into my eyes, with that same rueful little smile, and shakes his head in wonderment.

‘It’s my twin brother. That’s who I’ve been separated from. I’ve got to say I didn’t know if I should come to visit you like this, but, well, you’re living up to all my hopes and expectations. So, can he say anything, my brother? Is there any message that he’s got for me?’

I’m sorry, but I can’t resist it, not when I’ve read all that rubbish on his brother’s blog.

‘Yes. Yes, there is. I’m not sure I can understand it properly, but I think Dennis wants to say that he was wrong. Does that make any sense? I’m sensing that he never thought there’d be an after-life, and that he might have had some harsh words about those of us who do. Is that an accurate impression, that I’m passing on? He’s saying he wants to apologise, and he knows better now. He says it’s wonderful, the place he’s in. He’s telling me that he’s been reunited with old friends. He says to tell you he’s with...Benjamin, or Benji? Is that right? Is that somebody that you used to know?’

To tell the truth, I threw that last bit in just on an impulse, but I’ve hit the jackpot, so to speak. He’s filling up. He’s staring at me and his eyes are wet. The little smile he had is gone.

‘Benji was...he was a Great Dane that we had when we were kids. Both of us loved him. But then, you know that already. Mr. Sullivan, to think that you could bring up a beloved childhood pet like that...you’re truly unbelievable. If I had any doubts about what kind of man you were before I came to see you, they’re all gone. And what you said, how Dennis was always so sure that there was no life after death and having to reluctantly admit that he was wrong, that all rings very true as well. That’s very much what Dennis used to be like. Very much the cold-eyed rationalist. It must have took him by surprise, his current circumstances, but if I know him he’d see the funny side as well.’

The little smile’s come back again. I’m not a one to brag, but I think we can chalk up this one as a victory for Ricky Sullivan. I’m wondering, if I offer a cup of tea and biscuits perhaps we can chat about his brother for a while and then I’ll see him out, ching, fifty quid, but no, he’s off again.

‘Am I correct in thinking that you said you’d do a house-call for a hundred pounds? I wasn’t certain earlier that it would be the proper thing to do, but like I say, that business about Benji, you’ve convinced me. You’re the right person to do this with. I mean, surely you’d get a clearer message, wouldn’t you, if we were in the actual house where Dennis lived?’

I’m nodding from the point where he mentioned the hundred pounds. Well, I must say, I hadn’t thought this sounded very promising when David Berridge rang up earlier. He sounded so nervous and hesitant I wasn’t even sure that he’d turn up, but listen to him now after he’s had a dose of what I call the Ricky Sullivan effect. He’s like a different person. He’s more confident. It’s like he’s made his mind up. I think that’s a measure of the magic I bring to a situation, just my personality.

‘Well, yes, I’m sure that it’d make things clearer. More vibrations with a visit, obviously. Were you after making an appointment, or was it tonight that you were thinking of? I mean, I don’t mind. With the bookings I’ve got coming up, tonight would actually be quite convenient.’

Meaning it’s better from my point of view if we go now while he’s still feeling the enthusiasm, rather than giving him time to change his mind. But no, he’s nodding. He looks eager.

‘No, tonight is good. Tonight is perfect. It’s not far. We could be there in twenty minutes.’

This is turning out to be a very profitable evening. For the house, I’ve still got plenty of material I haven’t used, their parents names and so on, so I can give him his money’s worth. I can give him a proper visitation. I wonder if I dare do his brother’s voice? It’s a safe bet that they’d sound very like each other, but you never know. His brother might have had a stammer or a lisp or something. We’ll see how it goes, play it by ear. He stands up from the sofa with his hands still jammed deep in his raincoat pockets...he’s not took them out the whole time that he’s been here. He must be feeling the weather even worse than I am...and I take my scarf and leather coat down from the peg out in the hall so I can let us out. It cost a lot the coat, but you should see it on. It makes me look much taller and much more mysterious, like somebody from out The X-Files or The Matrix.

I shepherd him out the door, and while I lock it after us I hear the phone go. It might be another client, so my natural impulse is to pop back in and answer it, but no. I’ll let it go. The answer-phone will pick it up, and anyway, if I’m that interested I can always call the landline when I’m out and see who left a message. When I put my keys back in my pocket I have a quick fumble and make sure I’ve got my mobile, safe inside a kiddie’s knitted bootie, which is what I keep it in. I turn round and venture a breezy ‘Right, shall we be off?’ but David, Mr. Berridge, is already out the open front gate and away along the street, so that I have to hurry to catch up with him.

Oh, but it’s bitter out tonight. It strikes right at you through your cardigan. I don’t think that I can remember a December quite as cold as this since I was little. It’s the kind of cold that takes you back, and with the fog it’s dreadful. I’d forgotten, but it has a smell to it, does fog. It’s like damp smoke or something, it’s less of a smell than it’s a miserable musty feeling in your nose. And there’s a sort of cold burn in your airways when you breathe it. To be honest, I’ll be glad to get the stuff with Berridge over with so I can get back home. It’s, what, just after eight now. Twenty minutes there and twenty back, another twenty for the business, I could probably be back in time for Q.I. I’ll admit, the humour isn’t always to my taste but you can find out all these interesting little facts, like how the sea-slug’s actually a form of cucumber if I remember right. Isn’t that fascinating? If only these sceptics, all these types like Mr. Berridge’s late brother, if they could just open up their eyes and see how marvellous and inexplicable God’s wonders really are, like with the nature and that, then perhaps they wouldn’t be so smug and certain when it came to voicing their opinions. Because that’s all that they are, opinions. None of us can really know for certain, can we, what awaits us on the other side? I must say, I wish Mr. Berridge would slow down a bit. Still, he’s keen. That’s the main thing.

We walk down the road beside the park and then cross that dual carriageway that’s at the bottom end. It’s funny, but for saying that it’s so near Christmas, there’s hardly a soul about. Must be the weather, keeping them indoors. Or the recession. People always look so worried and so tense this time of year. It’s very stressful, isn’t it, trying to live up to everybody’s expectations? Not that I find it a problem, Christmas. To be honest, I always look forward to it. I mean, ever since my mother passed I haven’t really anyone to buy for, so it’s not a great expense. I know that for some people it’s a very lonely time, and that it’s when you get most of the suicides and that, but speaking personally I always find I get a little bulge in clients and consultations around January, so it’s an ill wind and so forth.

There’s kebab-shop neon and occasionally a set of headlights burning through the fog. We walk along by the dual carriageway for a few minutes, then we cross another main road that runs off downhill. I’m too puffed keeping up with him to make much of a go at conversation, but it’s not like there’s an awkward silence. We’re just eager to get where we’re going, for our different reasons. He’s thinking about his brother and I’m thinking about Stephen Fry and that hundred-and-fifty quid.

You know, in all the years I’ve lived where I am now, I’ve never had much cause to come down this way previously, and never as far as this. It’s what I think of as one of the rougher neighbourhoods, where most of it’s all tower blocks but where you’ll get the odd building going back to Cromwell’s time or even earlier. I don’t know why they don’t just pave it over, put a precinct up or something, with some nice pavement cafés. It’s probably the riff-raff down here with their tenant’s rights and everything that’s stopping it from happening. I know that this sounds awful, but if we have a bad winter, what with all these cuts, it might thin out some of the obstacles around these parts and end up being the best thing that’s ever happened to the district. There. I’m sorry, but I’ve said it.

If you want the honest truth I think it’s areas like this that are the real ghosts, aren’t they? Mouldy old things, dead things from hundreds of years ago that have no right to still be making an appearance in the present day, with all their creaking woodwork and their rattling chains. These terrible young men with their pale, undernourished faces and their hoodie tops, like apparitions, like the monk in Mr. A.S. Palmer’s photograph. Shrieks in the night and phantom bloodstains on the paving slabs outside a takeaway that will have disappeared by the next afternoon, it is, it’s like a gothic novel. And just like a ghost, a neighbourhood like this will hang around for centuries with all its flapping rags and its depressing atmosphere. It’s an accusing presence, making everyone feel guilty about things that happened before most of us were born. It’s not our fault if people were too lazy to make something of themselves and find a better place to live. Leave us alone.

Oh, look at that. A great big lump of dog’s mess on the pavement. That’s disgusting. I’m lucky I spotted it, what with the fog. If Dennis Berridge had to live round here, all I can say is that he can’t have been much of a physics teacher. Or perhaps he was, but never got on in the education system as it is now. Either way, it must have made him bitter that somewhere like this was all he could afford. Reading his blog, I sensed he was a very angry man. You’ll often find that people who say nasty things about spiritual healers, which is how I see myself, you’ll often find that it’s their own frustrations and their failures that they’re really cross about, deep down inside. His brother David here, though, seems much more contented in himself, more open-minded and more likeable. Walking a pace or two ahead he turns and glances back across his shoulder at me with his funny smile that, frankly, in the useless lamplight that they have down here, is looking a bit ghastly. Doesn’t look like a vessel of light, let’s put it that way, but you must remember that he’s had a blow, the poor soul.

‘Not far now. Dennis’s house is just along the end here.’

Well, thank God for that. If we’d have had to go much further, I think I’d have wanted rabies shots. I’m sorry, but I would. This street we’re on, it’s like a terraced row with little badly-kept front gardens, most of them with the gates hanging off or missing altogether. David takes a right turn up the pathway of a pebble-dashed affair and I follow behind him. The house looks to be in a better condition than the other properties along here, although not by much. It’s shabby, and the paint’s all peeling off round the front doorway, but at least its windows aren’t smashed in and patched with plasterboard like that house that we just passed two doors down. Someone had drawn a willy on its wood fence with black spray-paint and it’s had, you know, the stuff, the droplets coming out the end. Who wants to see that? They’ve got ugly minds, some people. Ugly minds.

‘I’ll tell you what, I’ll just check round the side to see that all the windows and back door are still alright since Dennis died. He kept a key under that flowerpot, next to the front doorstep there. Let yourself in, and if they’ve cut off the electric there’s a big torch in the passage, just inside the door.’

This is a bit irregular but, still, a hundred pounds. I have a job finding the plant-pot in the dark and then my fingertips are that cold that they’re numb, so that I’ve only just unlocked the door and found the torch that Mr. Berridge mentioned when he’s back from his inspection, standing there behind me. I can’t see his face in this light, but I know he’ll have that weary, gormless smile showing his rabbit teeth, that little overbite he’s got. I switch the torch on and it throws a puddle of tea-coloured light along the passageway, so I can see the bottom the stairs. I think that’s...no. Is it? I think that’s the old-fashioned stair-rods showing, brass ones like they used to have. That’s shameful. You’re not telling me a science teacher couldn’t have afforded to splash out on fitted carpets?

Mr. Berridge slips in past me, and I notice he leaves me to shut the door behind us, thank you very much. Born in a field, as my mum used to say. Not that shutting the door has made a scrap of difference to the cold. If anything, its colder indoors than it was outside and there’s that smell, the smell of other people’s houses. With the better sort of residences you don’t notice it, they all just smell of Glade or something, mine does, but in poorer people’s houses you can smell all the fish fingers and the dirty socks going back years, like it’s accumulated in the furniture. I try the light-switch in the hall, but nothing happens. I doubt that the council would cut somebody’s electric off so soon after they’d died, so probably what happened was he hadn’t paid his bill. I think it’s better if I hurry things along a bit, get to the business, so to speak. I don’t want to spend too long here.

‘Well, now, this is very atmospheric, Mr. Berridge. Very atmospheric. I can almost feel Dennis’s presence, as if he were right here next to me. I sense that he’s concerned about you, worried that you’re suffering needlessly over his death. He’s saying that he doesn’t want you to be hurt.’

I angle up the torch-beam from where it’s been playing over the unappetising wallpaper and the chipped skirting board and there they are, the goofy teeth and mournful smile as he considers.

‘Yes, that sounds like Dennis. We were always ever so protective of each other, being twins. If either of us were in any trouble or had someone picking on them, then the other would be on it like a ton of bricks. Dennis particularly. Out of us two, Dennis was always the bloody-minded one.’

Why am I not surprised? Anyone who can fume for pages about chiropractors and the like is hardly likely to be someone normal who just lets things go. I’m frankly glad I never met him. He sounds like a nightmare.

‘He sounds like a lovely, very caring man. Just let me ask you, was there a possession or an object Dennis was especially attached to, something I could touch? I find it often makes the contact stronger, that’s all. It could be a favourite pair of slippers or a record he was fond of. Literally, it could be anything. Just something so I can make a connection with him.’

There’s the smile again. It’s probably the torchlight bouncing round this narrow passageway, but it looks almost pitying, or even condescending. Oh, it’s very cold in here. It’s icy.

‘Well, if you want something so you can connect with Dennis, I think if I popped upstairs a minute I might come back with the very thing. Go in the living room and make yourself at home.’

He turns and walks towards the stairs, then he looks back at me, and...no. No, his voice is very faint and I can hardly make it out. He’s asking if I’d like...don’t know. A cuppa? Is he offering to make a cup of tea? I shake my head, smiling politely.

‘No, no, I’ll be fine. You go ahead and I’ll wait in the living room.’

He turns and walks up the stairs very casually for saying there’s no lights on, although obviously he’s more familiar with the place than I am. I’m guessing he’s spent a lot of time here.

I push the door open and I sweep my torch around the living room. God, this is a depressing little hole for somebody to spend their final years in. There’s three bookshelves, mostly science and science-fiction from the look of it, and there’s no television. Two sagging armchairs with one each side of an old three-bar fire. I’ve not seen one of them in years. Upstairs I can hear Mr. Berridge walking back and forth as he looks for whatever piece of sentimental tat he’s going to bring back down for me to go into my Vulcan mind-meld with. It’ll be Richard Dawkins’ autograph, I shouldn’t wonder. If he’s going to be a while then I suppose I could risk sitting on one of the chairs and rest my feet after that walking. I hope he’s not long. It’s 25 to nine already and I’m going to miss the start of Q.I. unless Mr. Berridge gets a move on. Sitting in the dark like this, well, it’s not how I like to spend my Friday evenings, put it that way.

Oh, hang on, there was that call I had when I was just locking the front door, wasn’t there? While Charley-Boy’s upstairs having a weep over his brother’s keepsakes I can at least check on that and see if there’s another client in the pipeline. Honestly, my fingers, fishing out the bootee with the iPhone in from my coat pocket, they’re half-frozen. If it gets much colder they’ll be falling off.

Dialling the number and the suffix that connects me to the answer-phone takes age. Clump-clump-clump upstairs, the footsteps through the ceiling. Thinking back, it didn’t sound like ‘cuppa’, what he offered me when he was just about to go up. It was more like ‘phantom’ or a word like that, except that doesn’t make...ah! Here we are. The girl’s voice tells me I was called at eight o’clock and then there’s the long pause before it plays the message.

Fanta. That’s what he said. ‘Ricky? Would you like a Fanta?’ But why should he...

‘Mr. Sullivan? I’m sorry, this is David Berridge. Listen, I’ve been talking to my wife and, well, I’m sorry, I’ve had second thoughts about coming to see you. I don’t think it’s anything that the departed would have wanted. I’m sorry to cancel the appointment and I hope I haven’t, like, put you about or anything. Anyway, thanks again, and sorry. Um, you take care. Bye. Bye....’

What? Is this...is he playing a trick or something, calling from upstairs, just some mean joke to make me...no, he didn’t call. It’s me who called, what am I thinking? It’s the landline, isn’t it? The landline at my house. I called and it said eight o’clock and he was with me then, outside my gate. There must be, I don’t know, there must be something that explains this, calm down, Ricky, something I’ve not thought of, and in just a minute I’ll be laughing at how daft I am. Because if David Berridge, if he rang at eight to call it off, if he’s still sat at home, then...

Up above me on the landing there’s a creak. Somebody’s coming down the stairs. I’m sorry.

I’m so sorry.

Alan Moore's Dodgem Logic has been colliding ideas to see what happens since November 2009. It's bi-monthly, and contributors include Stewart Lee, Josie Long, Graham Linehan, Robin Ince, Kevin O'Neill, Melinda Gebbie, Steve Aylett and many more. To find out more visit the Dodgem Logic website, where you can buy the latest issue, as well as back issues and merchandise.

Alan Moore's Dodgem Logic has been colliding ideas to see what happens since November 2009. It's bi-monthly, and contributors include Stewart Lee, Josie Long, Graham Linehan, Robin Ince, Kevin O'Neill, Melinda Gebbie, Steve Aylett and many more. To find out more visit the Dodgem Logic website, where you can buy the latest issue, as well as back issues and merchandise.

See Alan Moore talking backstage at Nine Lessons and Carols for Godless People, 2009.

In the old black-and-white plate, the pool of shadow on the left of the ghost’s face uncurled its legs to scuttle for the margin and the cluttered desk beyond. I shrank back in my seat and, no word of a lie, I genuinely felt it. It was over in a second when I realised it was just a garden spider come indoors out of the cold, what had been camouflaged against the dark bits of the photo, but I really felt that sort of tingle up the spine that all my clients go on about, so I know what they’re saying. I can empathise with them. It’s not all acting.

In the old black-and-white plate, the pool of shadow on the left of the ghost’s face uncurled its legs to scuttle for the margin and the cluttered desk beyond. I shrank back in my seat and, no word of a lie, I genuinely felt it. It was over in a second when I realised it was just a garden spider come indoors out of the cold, what had been camouflaged against the dark bits of the photo, but I really felt that sort of tingle up the spine that all my clients go on about, so I know what they’re saying. I can empathise with them. It’s not all acting. Alan Moore

Alan Moore